The Wall Street Journal | Op-ed | October 23, 2016

Yale University’s motto is Lux et Veritas, light and truth. But at Yale today, bureaucrats charged with investigating and punishing alleged sexual misconduct seem less interested in truth or fairness than in scoring political points.

To start, they have expanded the terms harassment and assault beyond traditional legal definitions. Under Yale’s sexual misconduct policy, sexual harassment includes verbal statements that have the “effect” of creating an “intimidating” environment. Sexual assault includes any contact without “positive, unambiguous, and voluntary” consent. According to Yale, consent must be “ongoing” at each stage of an encounter but “cannot be inferred from the absence of a ‘no’ ” or presumed from “contextual factors.”

With these expanded definitions in hand, “independent investigators”—eager to justify their employment by a university desperate to appear tough on sexual misconduct—rush off to find evidence of violations. They build dossiers on professors’ offhand comments made decades earlier. They probe the murky “he said-she said” of drunken hook-ups seeking to prove that consent was not freely given, irrespective of whether a crime has been committed. Administrative tribunals, lacking due process protections provided in a court of law, determine guilt and mete out punishments that forever label people misogynists, harassers, or perpetrators of sexual assault.

Just ask Jack Montague, former captain of Yale’s men’s basketball team. Mr. Montague was expelled from Yale in February after one such tribunal decided that a fourth sexual encounter with a female student, known only as “Roe,” constituted “non-consensual” sex. According to Mr. Montague’s attorneys, Yale bureaucrats decided to investigate the basketball star after hearing secondhand that Roe had “a bad experience” with him more than a year earlier—a fact the university does not deny.

One of Yale’s Title IX coordinators then spoke to Roe (who had not previously reported the alleged assault to the New Haven or Yale police or to Yale bureaucrats), after which she made an informal statement about her experience. A Yale Title IX coordinator, not the alleged victim, then filed a formal complaint against Mr. Montague.

In June Mr. Montague sued Yale in federal court in Connecticut, claiming the procedures used to convict and expel him were biased, unfair and caused damage to his reputation. Last month Yale answered Mr. Montague’s lawsuit firmly denying any wrongdoing. The case is expected to be heard early next year.

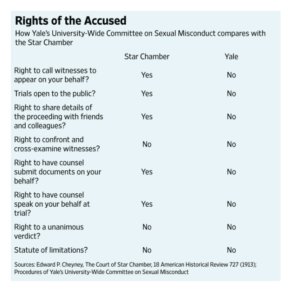

How bad are the procedures used by Yale to convict Mr. Montague—and dozens of other students and professors accused of non-consensual sex or verbal micro-aggressions? So bad that such traditionally liberal organizations as the American Association of University Professors have compared the procedures used by universities like Yale to those of the Star Chamber.

History buffs will recall that the Star Chamber was used in England in the 16th and 17th centuries to crush political and religious dissent. The Founding Fathers regarded the secret and arbitrary Star Chamber as so unfair that they crafted many of our constitutional protections precisely to avoid its abuses. And yet, centuries later, Yale’s University-Wide Committee on Sexual Misconduct employs procedures eerily similar to those of the Star Chamber.

For example, like the Star Chamber and other tribunals of the time, Yale’s sexual misconduct committees do not apply any statute of limitations and, thus, have the power to probe allegations that are years or even decades old. Yale’s arbiters of sexual misconduct, like the judges of the Star Chamber, determine guilt by a majority vote, rather than by a unanimous vote of a jury of one’s peers required in criminal courts to protect against the likelihood of wrongful conviction.

For example, like the Star Chamber and other tribunals of the time, Yale’s sexual misconduct committees do not apply any statute of limitations and, thus, have the power to probe allegations that are years or even decades old. Yale’s arbiters of sexual misconduct, like the judges of the Star Chamber, determine guilt by a majority vote, rather than by a unanimous vote of a jury of one’s peers required in criminal courts to protect against the likelihood of wrongful conviction.

Perhaps most concerning, Yale’s courts of sexual misconduct do not allow accused persons to cross-examine the witnesses against them. This, despite the fact that American courts have long found the ability to cross-examine witnesses to be a critical component of due process, particularly where, as in Mr. Montague’s case, the credibility of contradictory witnesses determines the outcome.

In many ways, however, Yale’s tribunals are less fair to the accused than even the dreaded Star Chamber, which allowed defendants to share information about the proceedings with friends and colleagues, call witnesses in their own defense, and bring along an advocate to speak and submit documents on their behalf. Mr. Montague was denied all of these opportunities.

Like many other universities, Yale determines guilt by a mere “preponderance of the evidence” rather than by the more exacting “clear and convincing evidence” standard traditionally used by universities in student disciplinary matters or proceedings involving faculty speech or conduct.

College administrators defend these kangaroo courts by saying they are complying with Education Department requirements. They point to the department’s infamous 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter, which, among other things, suggested that colleges and universities that failed to adopt the lower standard of proof in cases of alleged sexual misconduct might lose their federal funding.

Never mind that the Dear Colleague letter is nonbinding, or that the Education Department has never followed through on its threat to withhold federal funds under Title IX. Fearful or ideologically motivated college administrators nevertheless rely on the letter to justify stacking the deck against the accused.

Perhaps, however, there is some Lux et Veritas at the end of the tunnel—not just for Yale, but for all colleges and universities.

In a scathing 89-page opinion in April, federal Judge F. Dennis Saylor IV rebuked Brandeis University for its “secret and inquisitorial process” adopted in the wake of the Dear Colleague letter to resolve claims of sexual harassment. Although the court held simply that the lawsuit against Brandeis for violation of due process could proceed, the judge lambasted the university’s failure to allow the accused student to cross-examine the complainant.

In May, on the heels of Judge Saylor’s decision, a bipartisan group of 21 law professors released a statement alleging that bureaucrats at the Education Department unlawfully expanded the nature and scope of how colleges must define and respond to allegations of sexual assault and harassment.

And last week, the Education Department itself found that Wesley College in Dover, Del., violated the rights of an accused student when it did not provide him a full opportunity to respond to charges, rebut allegations, or defend himself at his hearing.

The sex tribunals at Yale and other colleges were created to address claims of serious misconduct on campus. The Star Chamber also was designed to address serious problems, including treason. Nevertheless, our Founders determined that Americans can and should adjudicate even the most heinous offenses using a system that preserves certain basic procedural rights. Surely, in the pursuit of light and truth, our universities should do the same.

Appeared in the October 21, 2016, print edition as ‘College Sex Meets the Star Chamber.’